On July 1, a company called Wildcat Intellectual Property Holdings, LLC sued 12 defendants, including Topps, Panini, Sony, Electronic Arts, Konami, Pokémon, Zynga and Nintendo, for allegedly infringing Wildcat's “Electronic Trading Card" patent. Wildcat's accusations could affect such online trading card products as Panini's NFL Adrenalyn XL and Topps' ToppsTown. Wildcat seeks unspecified damages and an injunction that , if granted, would require these online services to be shut down.

For those avid technology fans, the patent's wording of claim 1 provides a great example of a collision of legalese and patent-ese that creates a seemingly meaningless sentence:

1. A system for the implementation of a trading card metaphor, comprising:

a disassociated computer program, consisting of a plurality of electronic trading cards (ETCs), each ETC corresponding to a disassociated computer code segment embodied in a tangible medium and having an electronic format that supports card scarcity and card authenticity.

This sentence, however difficult to read, outlines the borders of the patent. I often translate legalese (or patent-ese) to spare the reader from such linguistic contortions, but because this patent claims “a trading card metaphor," I thought the language needed to be shared. You see, I am a lawyer accustomed to wading through patent claims that would drive most people crazy. Heck, today I was deciphering software claims for data storage and Internet security verification (zzz…), so I know a bit about reading claims. But until today, the only time I'd ever discussed “metaphors" was in a long-forgotten English class. I didn't know there were real-world metaphors. Thankfully, they're not claiming a simile (which if I remember correctly is a metaphor that uses “like" or “as"), or else I'd really be lost.

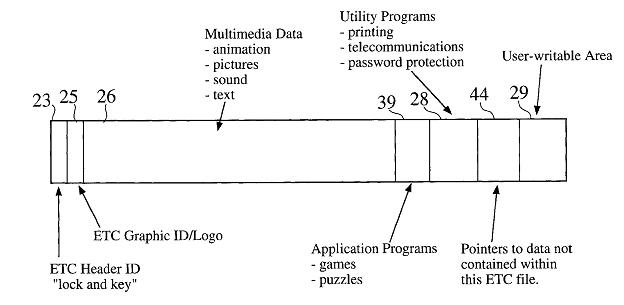

Anyway, although the patent is entitled “Electronic Trading Card," I think a more appropriate title would be “Virtual Trading Card." At its most basic level, the Wildcat patent appears to cover “disassociated computer code segments." This is basically an overly techie way to say virtual trading card. Figure 1 of the patent shows one of these electronic/virtual cards (at least, the format of one):

The format of the card (the programmed code segments) determines the scarcity and authenticity of the card and allow users to electronically trade cards, play games online, etc. In other words, some cards will be programmed to be scarcer than others (i.e., no more than a certain number of people can own the card). They could also allow interaction with certain games, in some circumstances, be changed and reprogrammed by the owner.

So, what's the best take home for collectors of “real," non-virtual baseball cards? This patent will not affect all of that cardboard you have in your closet. However, it could affect the future direction of the hobby. Trading cards have evolved a lot over the last 15 years. With the pervasiveness of the Internet, it is only a matter of time before cardboard cards further blur into the virtual world. This case may help define and clarify, who, if anyone, owns that crossover.

It's notable the lawsuit was filed in the Eastern District of Texas, a forum that patent plaintiff's enjoy more than most because it has assessed some of the largest patent judgments on record. Also, Wildcat appears to be what is traditionally called a non-practicing entity. In other words, another entity – person, business or otherwise – created Wildcat with the sole purpose of owning and enforcing the patent. Wildcat doesn't make electronic trading cards.

This occurs more often than you might think because inventions are often developed by small companies who, although they have the good idea, don't have the money to compete with the big boys. When large companies infringe on their patent, there is little that these small companies can do by themselves. They don't have enough money to sell a product, let alone sue multimillion- or billion-dollar competitors.

One way to level the playing field, however, is to sell the infringed patent to a larger company that specializes in enforcing intellectual property. This larger company acts like a big brother on the playground (A SIMILE!). Because it's a big company used to dealing with other large companies in litigation, it won't be bullied by tactics that would beat down smaller companies. To protect itself, the big brother then creates and funds the non-practicing entity company to enforce that patent. The real inventor retains a stake in the results of the litigation, while its big brother finances it. From looking at the court filings here, it's difficult to determine exactly who Wildcat is, but during the suit, that will likely come out.

The best predictor of how a patent suit will unfold is the Markman hearing. This hearing is where the court translates the asserted patent claims into English for a jury's benefit. In this case, the court will determine how this virtual card patent affects the real world. Judging from the claim language above, this is definitely one of those patents that will need to be translated into English for the jury to understand. Heck, I think I need someone to translate it to me! Because this suit was just filed, however, it is months away from a Markman hearing.

Defendants in patent suits tend to settle in stages. There's normally an initial push by defendants to offer a smaller settlement amount than what it would cost to defend the suit. Because most patent suits are expensive, regardless of the companies' view as to whether the suit has merit or not, this is a wise choice. Why spend $2 million defending yourself, when you can settle for $100,000?

The second stage of settlements typically follows right after the Markman hearing, because that is when both sides should know which way the jury will rule. The final stage of settlements occur between summary judgment (where the judge decides if there is sufficient basis for a trial) and trial. Most suits (well, more than 90 percent) settle before going to trial, so odds favor this one will too (and confidentially, so the public will be none the wiser as to whether there is infringement, or the terms of the settlement).

The next round of action in this case will take place in 30 to 60 days when the defendants respond to Wildcat's complaint. I am looking forward to seeing if these filings shed any more light on the case or on the meaning of the “trading card metaphor."

And if you missed it, “light" is the absolute metaphor for “truth," (thank you Wikipedia) so I guess I do understand metaphors…maybe just not a “trading card metaphor."

The information provided in Paul Lesko's “Law of Cards" column is not intended to be legal advice, but merely conveys general information related to legal issues commonly encountered in the sports industry. This information is not intended to create any legal relationship between Paul Lesko, the Simmons Browder Gianaris Angelides & Barnerd LLC or any attorney and the user. Neither the transmission nor receipt of these website materials will create an attorney-client relationship between the author and the readers.

The views expressed in the “Law of Cards" column are solely those of the author and are not affiliated with the Simmons Law Firm. You should not act or rely on any information in the “Law of Cards" column without seeking the advice of an attorney. The determination of whether you need legal services and your choice of a lawyer are very important matters that should not be based on websites or advertisements.

|