This is the first in a two-part series that analyzes the suit Topps brought against Leaf on Aug. 11, 2011.

Last week, Topps brought suit against Leaf alleging Leaf's 2011 Best of Baseball infringes various copyrights and trademarks owned by Topps. There are several reasons why, if asked to represent Topps, I would pass on this case as a plaintiff's attorney.

I started my legal career at a large defense firm. There, I advised larger corporations on how to avoid troublesome copyrights, patents and trademarks owned by other companies. Or, if my clients got sued, I tried to help them get around those same copyrights, patents and trademarks.

Now, I help plaintiffs assert copyrights, patents and trademarks against larger companies that infringe on their intellectual property. My former defense firm life, while a 180-degree shift, is invaluable to my current work, because it helps me with my due diligence.

Basically, it allows me to put any potential new case through a war game so that I can assess whether the new case is worth the risk. Since the majority of the cases my firm takes are on a contingent fee basis (meaning, we only get paid if we win or settle the case), the cases we bring have to be strong. Otherwise, my firm could lose thousands (if not millions) of dollars.

This aside is a long-winded introduction into the Topps vs. Leaf lawsuit because, what I'm going to do here is put the Topps' case through a due diligence process and show you exactly why if this case was offered to me on a contingent fee basis, I would pass on it.

The strength of this suit is debatable. This is not to say the case lacks merit; I'd take this case if the client paid on an hourly basis. I mean, heck, it's Topps. Could you think of a cooler company to represent? But the risks on this case seem to outweigh a potential monetary reward. For that, this case would not be a strong case on which I would bet my firm's money.

A Buyback Card Fight

Topps filed this suit because each pack of Leaf's 2011 Best of Baseball has a professionally graded buyback card. While lacking a strict definition, buyback cards refer to cards that were previously circulated in other sets. Sometimes these cards are “bought back," repackaged and then redistributed. Other times, the cards may never have been circulated themselves (i.e., unclaimed redemptions) when the product originally came out. In addition, buyback cards are not always bought “back" by the company that made them. Sometimes other companies buy cards and insert them into their own packs.

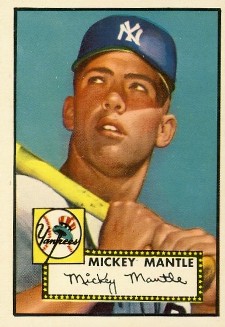

The Topps' complaint focuses on Leaf's sell sheet for the product that shows collectors which buyback cards they could pull. Topps' issue with the sell sheet is that 11 of the 18 cards pictured are Topps cards including a 1952 Topps Baseball Mickey Mantle (the “holy grail" of all baseball cards), 2001 Bowman Chrome Baseball Albert Pujols and a 2010 Bowman Baseball Bryce Harper autograph. In case you have lived under a rock and do not know what a 1952 Topps Mantle looks like, here you go:

Yes, you should recognize this card. It's probably the most famous baseball card ever made.

Topps claims Leaf's sell sheet utilizes copies of Topps cards without Topps' permission. This constitutes copyright infringement. Topps also claims that Leaf's use of Topps or Bowman trademarks (i.e., the trademarks marked on the cards themselves) constitutes trademark infringement. Additionally, Topps claims that Leaf's use of the likenesses of players exclusively licensed to Topps (Mantle, Harper, Strasburg, etc.) is likely to confuse consumers as to who is behind the 2011 Best of Baseball product.

The lawsuit mostly focuses on the sell sheet, or other advertising and packaging that may display Topps' cards or trademarks. It is not, at this time, a suit against buyback cards, although there may be room for Topps to try to escalate the battle.

Infringement or Not?

Now, that the background is out of the way, let's walk through my “war game."

The first step is to determine if the case is winnable. In other words, there has to be infringement and no viable defense to infringement. The second step is to decide whether the amount of money that could be won would be worth the time and monetary risk that a contingent fee firm would put into a suit.

Topps' copyright infringement claim is the easiest to explain, so we'll tackle that one first. To prove infringement Topps needs to show a) Leaf had access to the copyrighted works and b) copying by Leaf. The sell sheet answers both questions with a resounding “yes". Leaf had access to the copyrighted cards (that's why they are buybacks), and it copied them by scanning them into a digital format (yes, scanning a baseball card is technically copyright infringement).

Is there infringement? Check.

Fair-Use Defense

While the case looks good so far, it's about to take a big hit on the copyright front because Leaf has some defenses: equitable defenses and the fair-use defense.

Leaf's equitable defense, although more complicated than what I will explain, works as follows – for years, Topps allowed people to use copies of its cards when selling their products, so Leaf should be able to do the same. Basically, because Topps gave everyone else permission by not going after them, they also gave permission to Leaf.

The best illustration of this defense is eBay.

eBay is the largest secondary market for trading cards. When selling cards on eBay, pictures of those cards are displayed. This requires the sellers to copy the cards with their scanner. As I stated above, this is technically copyright infringement.

I am unaware of any trading card company enforcing its copyrights against eBay sellers. In fact, a search on eBay for “Topps," limited to just “cards" yielded more than 1.5 million items for sale. It's safe to say that more than 90 percent of these listings display a copy of the card. In other words, there are currently over a million potential copyright infringements going forward on eBay and Topps is doing nothing about it.

Leaf's argument would be that Topps cannot assert an infringement claim against Leaf because by allowing the million or so other current infringers to do the same (not to mention the millions of prior infringers over the last 10+ years) is unfair. Basically, Topps abandoned the right to enforce its copyright in this manner through its years of inaction.

Leaf's fair use defense works in the same vein. Leaf is lawfully in possession of the buyback cards. This is because of the “first sale" or “exhaustion" doctrine which allows “the owner of a particular copy…lawfully made under this title…is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to sell or otherwise dispose of the possession of that copy." In other words, once you legally obtain a copyrighted work, you can do anything with it you want (so long as you don't copy it). Companies cannot limit what you physically do with the card. If you wanted to resell it, frame it, or cut it into pieces, you could.

A Different Type of ‘Possession is Nine-Tenths of the Law' Defense

The other part of Leaf's copyright defense (the fair use defense) is pretty basic. Because Leaf is lawfully in possession of the buyback cards, it can dispose of them anyway it wants. So, it wants to include them in 2011 Best of Baseball. The fair use defense is practical because the only way Leaf can show consumers what they could potentially pull from a pack is to show a picture of the exact card on the sell sheet.

Both defenses are strong. While they may or may not carry the day, they are definitely challenges to Topps' claim. So, given the risks, this claim will only survive a due diligence analysis if the damages greatly exceed the risk.

What are the Damages?

Here, actual damages are speculative. How much is Topps actually hurt? Or how much does Leaf stand to make due to its copying of these specific images? Probably, not much. Topps can, however, elect statutory damages that could be as high as $150,000 per copyright. Since there are multiple copyright registrations at issue in this suit, that could give a maximum recovery of over a million dollars. This does not include potential attorney's fees and costs. However, this million-dollar recovery would be a grand slam. Judges have great discretion on the amount of statutory damages, and it's unlikely, given the fact scenario (Leaf does not appear to be a bad guy, and it has significant defenses), that a judge would max out the damages.

With risk on the claim of liability, and speculative damages, the copyright claim by itself is too risky for a contingent fee case. Combining it with a valid trademark claim could still make it worthwhile.

We'll tackle the trademark claim tomorrow.

The information provided in Paul Lesko's “Law of Cards" column is not intended to be legal advice, but merely conveys general information related to legal issues commonly encountered in the sports industry. This information is not intended to create any legal relationship between Paul Lesko, the Simmons Browder Gianaris Angelides & Barnerd LLC or any attorney and the user. Neither the transmission nor receipt of these website materials will create an attorney-client relationship between the author and the readers.

The views expressed in the “Law of Cards" column are solely those of the author and are not affiliated with the Simmons Law Firm. You should not act or rely on any information in the “Law of Cards" column without seeking the advice of an attorney. The determination of whether you need legal services and your choice of a lawyer are very important matters that should not be based on websites or advertisements.

|